A Guide to Editing Your Own Book

First of all, congratulations! If you’re looking to learn how to edit your own novel, it means you’ve finished it! Take a moment to revel in your accomplishment. Finishing the first draft of a novel is not an easy feat. To make it this far, you’ve had to show your perseverance, creativity, and problem-solving skills. Now you’re ready for the next step: self-editing your fiction manuscript.

Before you submit your finished book to an agent or publisher, use these self-editing tips for story and grammar to present it in the best light and help you tell the story you intend to tell. If you’re opting for self-publishing instead, editing your book in advance will save you money and also deliver a better book to your readers. Ready to get started?

How to Edit Your Own Novel

You’ve heard the often-repeated advice to put distance between yourself and your finished manuscript before jumping back in and editing. While it helps to view your writing with a fresh eye, I find that giving myself the excuse of time is the same thing as giving myself an excuse to put it off. It disturbs my momentum. Distance is good for helping me catch small grammar errors once a project is nearly done. With a little time for forgetfulness to creep in, I am able to make myself read what’s on the page rather than filling in the gaps with what I intended to be on the page. But no novel is ever “done” after the first draft.

A manager at my recent content editing job asked me once if I liked writing or editing better. I replied that in a way, they are both the same thing. Writing is editing. Editing is writing. Both involve manipulating words to say what you want them to say in the way you want to say them. Typically writing is the discovery phase, but important discoveries happen while revising, too.

When it comes to editing, as with writing, there are no hard and fast rules to follow. You do what works best for you—for your timeline, your skill level, and your story. But you need to edit. No writer has ever sat down and produced a masterpiece on the first go. The characters, lines, conflicts, and plot points you enjoy in your own reading are the product of thoughtful revision. Sometimes the story elements only come fully together once they’re already down on the page because the very act of rereading them clues the author into some new idea.

Editing vs Revising

When working on my own manuscript or short story drafts, I use these two words—editing and revising—more or less as synonyms. There isn’t a clear line of delineation between editing for grammar and revising a book because there is just so much overlap.

This is my process: first, I sit down and reread what I’ve written. I remove or rewrite sections or chapters. I take notes on what doesn’t work and search for solutions. Then, I correct typos and swap out words that don’t mean what I want them to for ones that fit better. I add description or metaphor where it occurs to me. Around this point, I complain to my husband about the places where my character’s motivation flags. Finally, I reread again, tracking my characters’ growth throughout the story, tracking the pacing of the escalating conflict. I repeat the process until I’ve reached a wall, or more likely, a deadline for my writing workshop group.

When you’re working on your own story, these two words likely mean the same thing. You’re taking all those individual pieces of a story and tinkering with them until you’re satisfied with the end result. That being said, when you work with an editor, these words do not mean the same thing. An editor will edit your manuscript (correct errors, point out things that don’t work)—but you, the writer, are the one who will do the revising.

Start with the Story: Developmental Editing

A developmental editor’s job is to read your story and make sure it works. Is your conflict sustained throughout the story? Do the characters act in ways that are believable given what we know about them? Does each chapter deepen the conflict and carry the story forward?

When you’re revising your own story, ask yourself these same questions to make sure the individual pieces function together to tell the type of story you’re trying to tell.

The following part of the guide on how to edit your own novel is based on some common story issues I’ve encountered while editing fiction manuscripts that you can fix on your own.

Weave your character’s backstory into action and conflict.

Every character has a history and a personality that shows who they really are. As tempting as it is to give that information up front, make sure you introduce your character in a way that fits into the story. Include details when they are relevant. If a tragic history they lived through doesn’t inform the scene at hand, save it for a moment where it will be more meaningful. A hint of a backstory with tension is often more engaging than a complete flashback. Show just enough about your character to give readers a sense of them and what’s important to them.

If you find any information dumps (exposition that isn’t part of the scene), determine which parts are most relevant and necessary to include. We have the whole book to get to know your characters. Prioritize description and history that readers wouldn’t be able to assume about your character over the typical things readers can assume. Let the reader use their imagination to fill in the gaps. Give us something to wonder about.

The same goes for setting.

If you’re writing a story that requires extensive world-building—especially fantasy or science fiction—make sure you break up that information and dole it out on a need-to-know basis. Use a scene or dialogue between characters to show us how things work in your fictional universe. That doesn’t mean to just have one character tell another the rules of your world. Clue your readers into these implicit rules naturally by having your protagonist encounter them in the wild. Remember, readers don’t need to understand everything all at once—we just want to feel a vague sense that there are rules.

Similarly, if there’s some complicated history we don’t need to know to understand the beginning of the story, give it to us later, preferably in chunks. Readers are more likely to stick with a story if they care about the characters or are intrigued by the conflict. I promise you that if you begin your story or interrupt the narrative with a history textbook explanation, readers will get bored, or worse, put the book down. Show us what matters through the plot, not at the expense of it.

Simplify anything you can.

If you have multiple scenes or side characters that fulfill the same purpose, this first stage of revising is a good place to condense them. For example, I had a scene where a character made two phone calls to different therapists. Why? Just because I had written it that way in drafting. It didn’t matter to the story at all whether my main character spoke to one person or two people, only that he said what he said. In revising, I combined these conversations into one.

The same rule applies for characters. If your character has a group of friends or coworkers, be sure you need all of them in the story. Having too many characters can confuse readers, especially if any of the following are true: they are introduced too close to each other, they are similar in speech, appearance, function or relationship to your character, their names start with the same letter, or they are not important to the story or conflict.

In the revision stage, you want to remove as many potential stumbling blocks for your readers as possible. Remember, you don’t always have to include everyone’s names off the bat. It’s perfectly fine to refer to characters as “his mother,” “the old man next door,” or “her grandfather” in a story where the main character would refer to them that way. This cuts down on the number of names, especially in novels with a big cast.

Make sure your conflict stretches the length of the story.

Often in novels, the main conflict doesn’t appear until a quarter of the way into the book. That early portion is spent introducing us to the character’s life before whatever comes along to disrupt things arrives. However, even in that introductory section, be sure to include some tension— a character’s personal conflict that shows us something about them or gives some hint of tension to come. A simple way is by giving your character some motivating factor and a goal. Even better: give them a goal that’s in opposition to someone else’s goal. It may not be the same goal they have later after everything changes, but it will give readers some direction as they get to know your character and the world they inhabit.

That conflict should span the length of the story. Then, after you resolve it, the end should be close at hand. Post-resolution, falling action should leave the readers with a sense of how the character will go on from here.

In contrast, if you’re writing a short story, your conflict should appear on the first page (typically) or by the end of the first paragraph (in shorter flash fiction). Then, by the time we reach the end of a short, readers should understand why this story was the moment in the character’s life the writer decided to show—as a fiction professor of mine repeated often, “Why today?”

Follow your character arcs to make sure they’re realistic and satisfying.

Grappling with the story’s adversary should uncover your character’s personal conflict and inspire them to change to confront it. In general terms, your character should grow over the course of the novel (in understanding, in mental or physical strength, in confidence) to become the hero who can tackle their adversary head on. If they already have everything they need at the beginning, there’s no story to tell. Your character arc is a process. Early on in the novel, your character should lose or make costly mistakes as a result of what they don’t know or can’t do yet. That’s what makes them believable. Their reaction to these struggles and the way they overcome them to beat out their conflict is what makes them protagonists.

Along with that, sometimes your protagonist has friends or accomplices that help them on their mission. These side characters may help them realize their potential, teach them things, or work alongside them. However, it is ultimately your protagonist (not their friend) who does the heroic thing at the end where they confront their conflict. Otherwise, readers will wonder why we didn’t get the side character’s story instead.

Eliminate unnecessary dialogue.

Dialogue should surprise readers. If readers know exactly how a character is going to respond, that doesn’t make for an interesting story or an interesting character. Their responses should be unexpected and true to that character. If anyone would respond the way your character does, chances are readers could skip the scene without missing anything. Everything in your novel should be essential. Make sure every line your character utters is in their voice and either teaches us something about them or propels the plot forward.

If your character experiences something and is then asked about it by someone who wasn’t present, don’t have your character describe a scene that readers just witnessed. Readers will trip to skip over it. You can refer to the events without summarizing them. If that’s not possible, consider summarizing parts of the dialogue with exposition instead.

For example:

“How was the date?” Jeffrey asked as soon as I was through the door. I popped open a beer from the fridge and dropped into one of the kitchen chairs across from him. “That bad?”

“Worse,” I said. Then I told him about it.

Save copies of your different drafts.

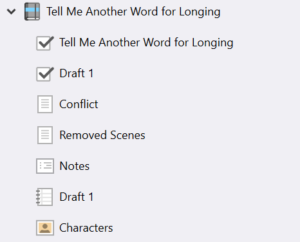

You never know when you might want to go back to a previous version of your manuscript. If you’re making major changes to a chapter, save a separate file to preserve your original. Consider a program like Scrivener that lets you view your manuscript in outline form or work in two different drafts (or two different chapters) at the same time. Another plus to Scrivener, it’s easy to keep various working drafts in the same document and toggle between them. It makes me feel better about the revision process to move my deleted scenes into another document rather than just erase them. That way, they aren’t gone forever if they just don’t fit into the section of the story I’m working on.

Catching Grammar and Sentence-Level Errors

After revising your manuscript to strengthen story elements, you should still read it through for grammar and clarity. It isn’t easy to self-edit your own work, especially if you’re a newer writer or struggle to remember some of the finer points of grammar rules. If writing is your passion, I recommend familiarizing yourself with grammar and syntax rules because knowing them gives you more control over your writing.

These are some tips I use when editing my own work and when I edit for other authors.

Read sections of your work aloud or use accessibility software that can read it to you.

If you stumble over a phrase while reading aloud, chances are readers will too. You might also want to try software that reads your work to you. Microsoft Word has a “Read Aloud” feature. A number of websites also offer this service for free. Try TTSReader or NaturalReaders.com which both have some features available for free.

Changing the font can help you pick up on skipped words, substitutions or other errors.

Change the font and/or font size of your entire manuscript before reading it back to yourself. This helps if you’ve already reread your book through a few times and have started to memorize your own words. Because humans have a very good memory of places, you might skip over phrases or words because your eyes are used to seeing them there where they are on the page. By changing their appearance, you disturb this pattern. Harder-to-read fonts also force you to read more closely than you might otherwise—letting you catch errors you might have missed.

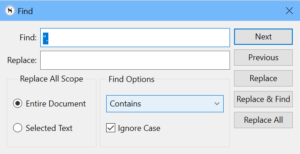

Search and “Find” errors you frequently make.

If you’ve ever worked with an editor and received feedback on “repeat offenders,” search for them in your document with your word processor’s “Find” feature. For example, you might struggle with correctly punctuating quotation marks. Search for these kinds of errors in your manuscript.

Use active verbs.

Use the “Find” feature to locate and highlight “to be” verbs in your writing: was, were, is, are. Then, see if you can substitute them for a stronger verb that better conveys tone and meaning. I also use this feature to look for helping verbs such as: looked, watched, saw, heard, etc.

Compare:

In the center of the ballroom, Leticia was dancing on the arm of a stranger. She had her hair pulled up and little pearls were decorating the coiled strands. They made her look like something out of a movie. The man wasn’t anything special. I saw he had on a black suit with a striped shirt underneath. But pinned to his lapel was a kind of flower I’d never seen before. Instead of soft rosy petals, it had long spidery legs. I wondered how a flower like that would smell.

In the center of the ballroom, Leticia danced on the arm of a stranger. She had her hair pulled up and little pearls decorating the coiled strands like something out of a movie. The man wasn’t anything special. He had on a black suit with a striped shirt underneath. But pinned to his lapel was a kind of flower I’d never seen before. Instead of soft rosy petals, it reached out with long spidery legs. How would a flower like that smell?

Pay attention to pacing and rhythm.

If you have too many long or short sentences in a row, consider varying them so the writing doesn’t feel monotonous. Chop longer sentences in two. Add an interesting detail to a short description to bring a different rhythm to the phrasing.

The same rule applies when sentences start with the same subject. This is a common issue in first person novels, especially if your narrator is performing a lot of the action. It helps to eliminate any actions that readers can assume and combine related actions where you can. Another option: vary the subject. Have your character notice something as they go about their actions. Then, make that thing the subject of the sentence, like Missy below.

Compare:

I climbed into my pickup and slammed the door. I could hear Missy still shouting at me from the front porch. I didn’t want to hear it anymore. I started the engine and drove until I reached the Super Walmart at the edge of town where Delphine worked.

I slammed the door of the pickup. From the front porch, Missy was still shouting, “Who is she? What’s her name? Tell me her name,” but I didn’t want to hear it anymore. The engine turned over without a hitch, and I drove until I reached the Super Walmart at the edge of town where Delphine tended the self-checkout.

Put time between yourself and your chapter.

If you’ve just completed some major revisions on a chapter of your novel, move on to another chapter before going back and editing for sentence level issues and grammar. You want enough time to pass that you can reread the section with fresh eyes and have errors and other points of confusion jump out at you.

How long does it take to edit your own novel?

It depends on how much time you have to devote to the process. Every novel and short story is different. It’s true that some come easier than others. Authors can spend a year or more rewriting and editing their work. This article on LitHub outlines the self-editing process of 12 famous authors (including JK Rowling and Neil Gaiman). It helps to remind me I’m not alone in this labor-intensive undertaking.

Hopefully you learned something new about how to edit your own novel. When you’ve finally slogged through your revisions, your manuscript will be ready for another critical eye. Beta readers and editors can catch things you missed and also provide expert suggestions on how to fix issues with your manuscript. Request a quote today!

Heather Hobbs is a fiction writer, editor, and avid reader.

If you have general questions about editing your own manuscript or are searching for an editor, reach out using the form below.